By Cat Troiano

Dementia is a collective term that applies to any condition that is characterized by a severe decline in mental capability. Alzheimer’s disease is one type of dementia, and it is the most common form, accounting for between 60 and 80 percent of all dementia cases. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, 5.7 million Americans are currently afflicted with this progressive and irreversible disease, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention projects that this figure will nearly triple, reaching 14 million by the year 2050.

Elusive Diagnosis

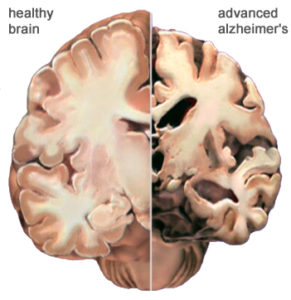

To date, there is no laboratory test available that definitively diagnoses Alzheimer’s disease in living patients. The only current option for definitive diagnosis is microscopic examinations of brain tissue samples from a deceased individual. These examinations reveal the presence of the characteristic amyloid plaques and/or neurofibrillary tangles. These formations are accumulations of specific protein deposits in the brain tissue. Their development is actually part of the normal aging process, but the abundance of plaques and tangles is significantly higher in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and their emergence tends to follow a distinctive pattern. So how can a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease be made when a patient presents with signs of cognitive decline?

Symptoms, Risk Factors and Rule outs

When a patient alerts his or her physician to symptoms of dementia, diagnosis is made through a thorough evaluation of medical history, family health history and neurological tests that assess the patient’s cognitive function. Signs of dementia include:

• Memory loss

• Difficulty performing mental tasks

• Confusing or forgetting dates, times, places or people

• Decline in visual perception

• Impaired reasoning and decision-making skills

• Deficits in basic communication and language skills

• Misplacing items and being unable to retrace steps to find them

• Changes in mood

Anyone can experience these signs once in a while, but when they occur with an increasing frequency that may threaten to interfere with one’s independence and ability to safely and successfully navigate through life’s daily activities, it is time to consider the patient’s potential risk factors for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Some risk factors include:

• Being of African-American or Hispanic descent

• Family history of Alzheimer’s disease

• Type 2 diabetes

• Hypertension

• High cholesterol

• Obesity

• Down syndrome

More women than men suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, and advanced age is certainly a factor to consider as well. However, while most cases of Alzheimer’s disease manifest after 65 years of age, individuals who begin showing signs of the illness at a younger age account for 5 to 10 percent of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Alzheimer’s disease is not a normal result of the aging process.

Not all cases of dementia are specifically Alzheimer’s disease. The initial laboratory tests ordered, which include a complete blood count, thyroid and metabolic profiles, are performed to rule out other conditions that can cause dementia. Diabetes, abnormal thyroid function, certain vitamin deficiencies, infections, electrolyte imbalances and excessive alcohol use can all contribute to non-Alzheimer’s forms of dementia. If any of these conditions are diagnosed, steps can be taken to treat or manage the condition and to prevent further cognitive decline. If none of these conditions are diagnosed, and if diagnostic imaging tests reveal no evidence of stroke, brain trauma or brain tumors, then there are a couple of genetic screening tests that can be ordered which may help physicians to make a more confident diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease.

APOE Genotyping

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is a genetic component of lipoprotein that is found in the blood. There are three forms, called alleles, of APOE, which are designated as e2, e3 and e4. The APOE gene, particularly the e4 allele, poses an increased risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. APOE genotyping, which is performed on a sample of whole blood, identifies the presence and combination of APOE alleles present. Rather than provide a definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, this test helps to indicate a patient’s genetic risk factor for developing the illness, thereby enabling a physician to make a likely diagnosis of the patient’s dementia symptoms. Approximately 65 percent of patients who are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease have one or more APOE e4 alleles. However, possessing the APOE e4 allele is not a requisite for developing Alzheimer’s disease. Many individuals can test positive for this gene without ever having the disease.

PSEN1

Alzheimer’s disease that develops in patients who are younger than 65 years of age is known as early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease, or Alzheimer’s disease type 3. Such cases tend to be hereditary, resulting from a genetic mutation. One genetic mutation that has been associated with between 30 and 70 percent of Alzheimer’s disease type 3 cases is a PSEN1 mutation. The PSEN1 gene is responsible for the production of a specific protein, presenilin 1, that aids in brain and spinal cord development. A mutation of this gene ultimately leads to the formation of amyloid plaques on the brain. PSEN1 is a dominant gene, and a developing fetus has a 50 percent chance of inheriting a PSEN1 mutation from the parent who has it.

The PSEN1 test, which is also performed on a sample of whole blood, may be ordered for patients who are less than 65 years of age and presenting with signs of dementia. The test may also be ordered for asymptomatic individuals who have family histories of Alzheimer’s disease type 3. Asymptomatic individuals that test positive for the mutation have a significant probability of developing Alzheimer’s disease type 3 at roughly the same ages as did their prior affected family members, but the presentation and progression of symptoms vary with each patient. Currently, there are more than 150 known PSEN1 genetic mutations, and the test does not identify all of them.

Prompt Testing for Extended Quality of Life

Researchers are tirelessly working to find a cure for Alzheimer’s disease. Until one is discovered, current treatment protocols can be implemented with the following goals:

• Slow the progression of dementia symptoms

• Maintain functional mental capacity for as long as possible

• Manage behavioral symptoms

• Enable the patient to plan and make decisions regarding his or her future care, living arrangements and management of legal and financial matters

These goals are most effectively achieved when Alzheimer’s disease is diagnosed in the early stage. Alzheimer’s disease progresses through three stages, which are mild, or early stage, moderate, or middle stage, and severe, or late stage. By addressing symptoms of dementia as early as possible, tests like the APOE genotyping and PSEN1 can increase the chance of making a probable diagnosis during the early stage. Patients who are diagnosed early may also benefit from opportunities to participate in clinical trials of emerging new treatments. While the tests are not perfect, the early diagnosis that they can provide for many patients is a valuable step toward extending quality of life.

Image courtesy of the Alzheimer’s Association